foreign policy:

foreign players

foreign states

and dignitaries

intergovernmental

organizations

international

non-governmental

organizations

non-state

violent actors

foreign policy

home

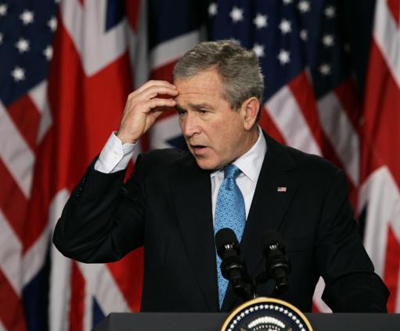

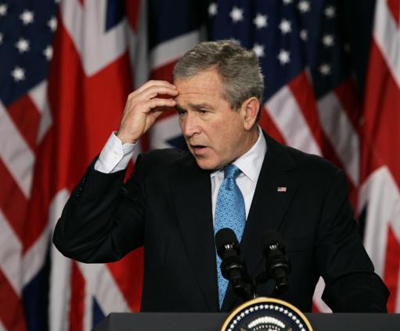

foreign states and dignitaries

Other countries and their leaders are probably the most obvious group that the U.S. has to interact with. How can relationships between countries be defined? There are a few questions that will help shed light on this:

- Does the United States recognize the other government?

- Does the United States have diplomatic relations with the foreign country?

- Are the diplomatic relations peaceful, conflictual, or somewhere in between?

1 |

To start off, does the United States recognize the other government? For example, John and Jane Doe might stage a violent uprising in Country X, taking over the government, which might anger the United States, causing them to refuse to acknowledge Country X as a legitimate country. President Wilson chose not to recognize some non-democratic governments, such as that of the Mexican dictator Victoriano Huerta. In current times, however, the U.S. tends to recognize all governments, but may choose not to deal with them.

|

2 |

This leads to the next question: does the United States have diplomatic relations with the foreign country? If so, the two nations will probably have embassies in their respective countries. The embassies house the diplomatic corps from each government, which facilitates communication between the two governments. Embassies retain the jurisdiction of their home country - so the American embassy in Paris, France is technically on American soil, so the French have no jurisdiction there. This international law helps provide autonomy and security to the State Department officials working at an embassy, and additionally provides traveling Americans with a safe haven of sorts should they need government assistance. There are times when this is not upheld, however, such as the 1979 Iranian Hostage Crisis when 52 American diplomats and citizens were taken hostage after some Iranian students invaded the American embassy in Tehran, Iran.

|

3 |

That begs the question: are the diplomatic relations peaceful, conflictual, or somewhere in between? What degree of trade is allowed between the two countries? What degree of travel? Is there an ongoing conflict? If so, are peaceful diplomatic measures sufficient, or does the situation require military force, or maybe economic coercion? Are the two countries allies or part of the same international group? Answering these questions will allow the relationship between two given countries to be well understood. |

intergovernmental organizations

An intergovernmental organization is a group made up of national governments. Such organizations are codified by treaties, and the member states are supposed to adhere to the policies of the intergovernmental organization. The nature of that government is typically limited, with minimal enforcement capacity. The specific purpose of an intergovernmental organization varies - economic agreements and collective security agreements are common. Intergovernmental organizations are another entity that a state will need to consider and interact with when forming foreign policy. Let's look at how intergovernmental organizations can influence foreign policy of member states and of non-member states!

Member States

Non-Member States

member states

A member state of an intergovernmental organization has agreed to act in accordance with the will of that group. Let's walk through two examples of membership in a collective security intergovernmental organization:

For example, the United States is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a conglomeration of states that have pledged to defend each other should a member state be attacked by a foreign power. Such an policy is referred to as collective security.

After the September 11th attacks, the U.S. called on its NATO partners to come to their aid. Now, the other members had a choice: do they help the U.S. as agreed upon, or do they choose to not uphold the agreement?

In this case, all members agreed to uphold the collective security agreement, carrying out multiple operations during the War in Afghanistan, including commanding the International Security Assistance Force.

This seems like the evident course of action - you agreed to come to the aid of a member country, so you should, right? In an ideal world, that's exactly how it would work, all the time. Let's look at another example:

France and the United Kingdom were both members of the League of Nations, a collective security organization formed after World War I. The tenants of this organization specified that if a state was attacked, the other members would attempt to negotiate a solution, and failing that they would use either economic sanctions or military force to come to the aid of the attacked state.

In 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria, China, who asked the League of Nations for assistance. When Japan did not leave Manchuria after attempted negotiations, the League decided to stop trading with Japan. In an ideal world, all the member states would cease trade with Japan, making it economically unwise to continue the invasion.

In reality, many member states refused to comply, due to poor domestic economies that would be hurt by economic sanctions.

One of the greatest failings of intergovernmental organizations is their lack of enforcement capacity, making it uncertain if the agreements of an intergovernmental organization will be upheld. Why would collective security agreements work sometimes, but not other times? It depends on a lot of factors. How much does the country have to gain by adhering? How much do they have to lose? What would be the cost of not upholding the agreement? Have the other member states all upheld it in the past? Would you need the other countries to help you if your country was under attack?

The takeaway: even if you are a member state of an intergovernmental organization, there is some uncertainty as to whether the other member states will uphold their end of the bargain. Given that, do you bother to join in the first place? Do you uphold the bargain yourself? This uncertainty is applicable to many types of intergovernmental organizations, such as economic organizations, although it is most easily visible in collective security agreements due to the comparatively high demands on members.

Non-Member States

Do countries that aren't members of a given intergovernmental organization need to concern themselves with it? Yes! Just like other countries, the actions of intergovernmental organizations can have an impact on other countries, even non-members. Let's consider an example of how the United States might need to adjust their foreign policy based on the actions of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC):

OPEC is an group of states that have some of the highest oil-production levels in the world. They collude on how much oil to produce, thereby changing the world oil market from competitive to quasi-monopolistic. What this does is allows OPEC to raise the world price of oil to a higher level than it would naturally be at without this collusion. There are a lot of non-OPEC countries that also export oil, and today their number is large enough to diffuse the power of OPEC a bit. Before large oil reserves were found in the West, however, OPEC had a massive degree of influence on oil prices.

Why did the U.S. care?

The government realized that higher oil prices were causing the Gross National Product (GNP) - a measure of the economic health of a country - to go down, and for unemployment and inflation to rise.

How does this impact foreign policy?

Clearly OPEC was negatively affecting domestic wellbeing, prompting politicians to call for reduced dependence on foreign oil. That means focusing on developing domestic supplies of oil and other fuel sources, like green energy. Specific to decreasing OPEC power over the price of oil, the U.S. could choose to import as little from those countries as possible, and as much as possible from other countries (cue calls for the creation of the Keystone Pipeline, which would increase import of Canadian oil). But at the same time, there are plenty of oil-rich countries that the U.S. disapproves of for one reason or another - Russia and Kazakhstan, for example. That opens the question of whether the benefit of decreasing OPEC power is worth the cost of aiding countries that the U.S. does not want economic ties with. The foreign policies of who to import from and who not to are tricky - and the intergovernmental organization that is OPEC gets everything just a little bit more tangled.

2013 U.S. Oil Sources

When will OPEC no longer be a major foreign policy concern?

Only if American can reduce dependence on foreign oil to zero. It's a politician's favorite foreign policy catch phrase: "We need to reduce dependence on foreign oil!"

International Non-Governmental Organizations

An international non-governmental organization (INGO) is a group unaffiliated with any government that works towards social goals, such as poverty alleviation, environmental causes, or humanitarianism. For example, CARE International works to fight poverty, including providing aid after natural disasters, which can have massive negative economic effects. Another group, Amnesty International, focuses on human rights, including opposing violence against women, the death penalty, and torture. There are also medical groups, such as Doctors Without Borders, educational groups, and even more specific project-oriented groups. Such groups normally focus their efforts on developing and underdeveloped countries, including regions in Africa, Eastern Europe, and Asia. They are frequently non-profits, but recently there has been an uptick in the presence of for-profit groups who argue that non-profits are too unsustainable.

There are several different ways that INGOs can have an impact on a country's foreign policy. An anti-torture group could lobbying governments, including the U.S. government, to cease the practice of rough prisoner interrogations. They could go as far as becoming a sort of muckraking journalist, exposing such incidents to the global eye, potentially putting the U.S. in a negative light. That possibility could very well affect the U.S. policy on torture, for example.

In a more positive light, an INGO could help a government carry out a desired foreign policy. For example, if the U.S. feels particularly strongly about decreasing poverty in Africa, they could choose to support an existing INGO that works in that field already, rather than spend valuable resources setting up a task force to do so.

non-state violent actors

A non-state violent actor (NSVA) is a mouthful that really just means a terrorist organization that isn't government sanctioned. Consider al Qaeda and the Afghani Taliban in 2001. Both are fairly unsavory groups, practicing various forms of violence, and housed in Afghanistan. However, al Qaeda is a NSVA whereas the Afghani Taliban is not. Why? Al Qaeda is a terrorist group that operates independently from any given state government. They were only operating out of Afghanistan at the time. The Taliban, while they could be violent and harsh, was the governing body of most of Afghanistan (all but about 10% in the northern region). Therefore, it would go in the category of foreign countries and dignitaries.

Click here to see why state-NSVA interactions are so tricky.

the difficulty of nsva-state interactions

The Policy Position

The U.S., especially post-9/11 is decidedly anti-terrorism, as are most Western countries. They also fear NSVAs carrying out terror domestically. That belief and that fear strongly shape American foreign policy. They trigger a strong sense of a need for national security, which has frequently led to anti-terror missions abroad. Less severely, countries that harbor NSVAs are typically seen in a very negative light by the United States, dissuading the U.S. from having extensive interactions with those countries.

Best Case Scenario

These types of groups are particularly tricky to deal with, as military or economic action taken against them inherently affects the country that they are operating out of. Sometimes this isn't a major factor. Soon after 9/11, it was clear that the Taliban government was actively shielding al Qaeda, and would not cooperate with the U.S. In that case, invading Afghanistan was not a problem.

Worst Case Scenario

But let's say that al Qaeda wasn't being sheltered by the Taliban, but rather they were hiding in the mountains without the Taliban's permission. The U.S. would still have wanted to use military force to punish al Qaeda for 9/11, but perhaps the Taliban government doesn't trust the U.S. to come into Afghanistan without trying to oust the Taliban after taking care of al Qaeda - the U.S. had never hidden their displeasure with the dictatorial government, after all.

The Conundrum

So what can the U.S. do without permission to send in troops? They can invade and likely be forced into a war with Afghanistan as well as with al Qaeda. They can use economic sanctions to try to throttled the power of al Qaeda, but that will also inherently affect Afghanistan. They can do nothing, but that leaves a wrong unpunished, and paints the U.S. as unlikely to retaliate in the case of future attacks. None of these options are appealing. The situation is complicated even more by the ability of NSVAs to flee a country, moving from hideout to hideout to avoid open war. This is much more difficult than fighting a county - a government is unlikely to flee their capital and country. Even if the people do flee, you've still won the country itself. Not so with a non-state violent actor. With the recent focus on the NSVAs in the Middle East, such as ISIS and Hezbollah, these seemingly unanswerable questions are going to become increasingly pressing.

Embassy Row, D.C.